Jewish life in Dresden after 1945

The last deportation transport from Saxony to Theresienstadt was prevented by the chaos following Allied bombing raids on Dresden on February 14. Around 70 Jews fled and went into hiding. Many of them took part in the re-establishment of the Jewish community at Bautzner Straüe 20 in the fall of 1945. Services were soon held again in the building, which is still used by the Jewish community today. Leon Löwenkopf (1892-1966) served as the first chairman.

The number of members increased rapidly and by the end of the 1940s there were over 200. The congregation's catchment area also included Görlitz, Bautzen and Zittau, where congregations only existed for a short time after 1945 due to insufficient membership. This involved, among other things, the maintenance of the Görlitz synagogue and orphaned Jewish cemeteries. One task of the Jewish community was the restitution of property that had been expropriated from the religious community during the Nazi era. The fact that this process was delayed was also due to resentment from the population. For example, an employee of the municipal garden office took offense at the loss of the Old Jewish Cemetery as a green space for the people of Dresden.

The Old and New Synagogue

A stele in the form of a menorah, created by sculptor Friedrich Döhner, has commemorated the Semper Synagogue, which was destroyed during the November pogroms, and the persecution of the Jewish population since 1975. Contrary to the inscription, the synagogue was 50 meters away from the memorial site, where the bridgehead of the Carola Bridge and a tram stop are located today. Whether the reason for this was negligence, greater visibility or traffic planning is unknown.

The consecration of the synagogue in Fiedlerstrasse on June 18, 1950 by the state rabbi Martin Riesenburger was the first consecration of a newly built synagogue (conversion of the former mortuary) after the Shoah in post-war Germany. While the synagogue initially had its own prayer leaders, guest rabbis and cantors such as the Leipzig senior cantor Werner Sanders soon came to Dresden.

1953 - persecution, flight and consequences

Jews who fled the GDR at the beginning of 1953 due to the anti-Semitic policies of the SED government included the community leader Leo Löwenkopf. His fate makes it clear that an atmosphere of unease had already prevailed beforehand. Löwenkopf, who had previously addressed anti-Semitism both publicly and within the SED, had already been imprisoned for three months in 1950.

Jewish women* had once again experienced stigmatization and traumatization, the loss of members intensified and most Jewish communities lost their chairmen. In Dresden, too, this initially led to a lack of direction within the community. Helmut Aris (1908-1987), a trained textile merchant, succeeded him as chairman in 1953.

A report by the People's Police, according to which members of the congregation behaved positively towards the GDR, but violated laws by „inciting people to flee the republic“ and „illegally receiving parcels from the West“, makes it clear that the Jewish community in Dresden was also being monitored by state authorities.

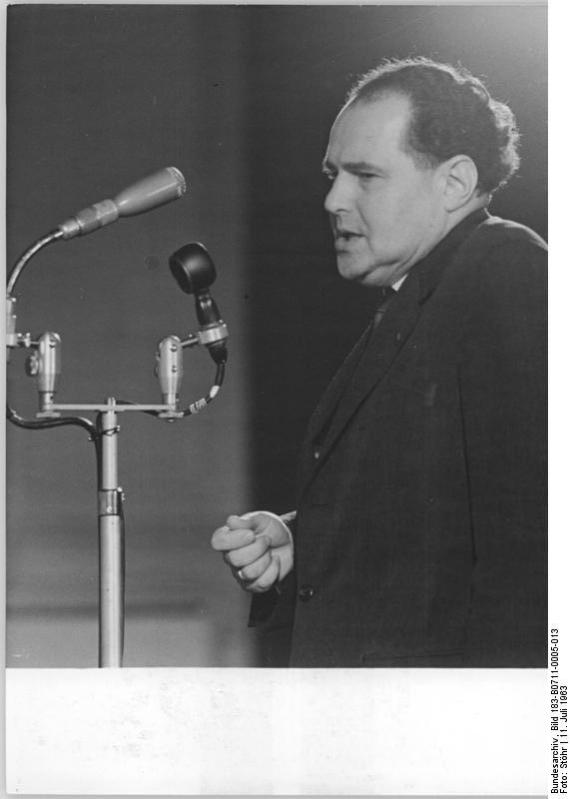

Helmut Aris – a Dresdener as president of the Association of Jewish Communities in the GDR

After the death of Hermann Baden (1883-1962), the members of the Association of Jewish Communities in the GDR elected Helmut Aris as the new association president on June 24, 1962. The association's headquarters were also moved from Halle to Dresden. From 1963 (until 1985), Dresden was also the location for central events of the umbrella organization. Since September 1964, the 1961 founded „Nachrichtenblatt“ of the Association of Jewish Communities in the GDR was published in Dresden. Aris was documented as an unofficial employee of the Ministry of State Security in the mid-1950s, but refused to report on members of the congregation. He criticized the GDR's denial of state anti-Semitism, for example by casting doubt on the results of the investigation into cemetery riots in Dresden. It was claimed that four-year-old children had knocked over the gravestones.

New awareness of Jewish history

It was only shortly before „reunification“ that Jewish history and the Shoah in the GDR gradually came to the attention of historians and the general public. One of the few who conducted private research in this field was Helmut Eschwege, who had returned from exile in Palestine. Eschwege's manuscript for a publication on synagogues in Germany in 1967 was withheld due to ideological reservations (he was expelled from the SED as a Zionist), so that his book could not be published until 1988. Nevertheless, he succeeded in ensuring that his findings on the subject of Jewish resistance under National Socialism - a research gap in West German historiography - were already being read by an international audience in the 1970s.

The fact that a new awareness of Jewish (local) history emerged at the time of the fall of communism is illustrated by the square in front of today's Johanneum. In 1992, it was given back its former name, Jüdenhof, which the square had held until it was renamed in 1936 as a reference to Dresden's first Jewish house of prayer in the Middle Ages.

Growth and immigration

For many Jewish remigrants, Jewish identity only played a subordinate role alongside their self-image as socialists. From the late 1970s onwards, many children of remigrants began to grapple with the question of their Jewishness.

From the 1990s onwards, the Jewish community in Dresden grew due to immigration from the countries of the former Soviet Union. This brought younger members who enriched religious life, but also new social and community-political tasks for the Dresden Jewish community.

Add new comment