The Early Modern Period (roughly the sixteenth to eighteenth centuries) was an era marked by radical sociopolitical changes affecting Jews.

After expulsions during the Middle Ages, Jews returned to live in the Holy Roman Empire beginning in the sixteenth century. Their residency rights were governed by letters of protection issued by the ruling kaisers, kings, and princes. These letters survive as testimony to the difficult legal status of Jews in the roughly 300 German territories.

Created in response to expulsions, Jewish self-administrative organizations called Landjudenschaften became increasingly common. Gemeinden, or official Jewish communities, were founded and organized, and these took responsibility for the financial distribution of Schutzgeld (protection money).

Very few Jews were granted permits to live in towns and cities. Such permits were usually only issued for a few years at a time, only to specific families, and generally required paying a fee or winning over a sponsor.

Many of the major trading cities refused to grant Jews residency, so Jewish traders often settled on the periphery of these cities. This expanded the Jewish communities of rural areas and small towns.

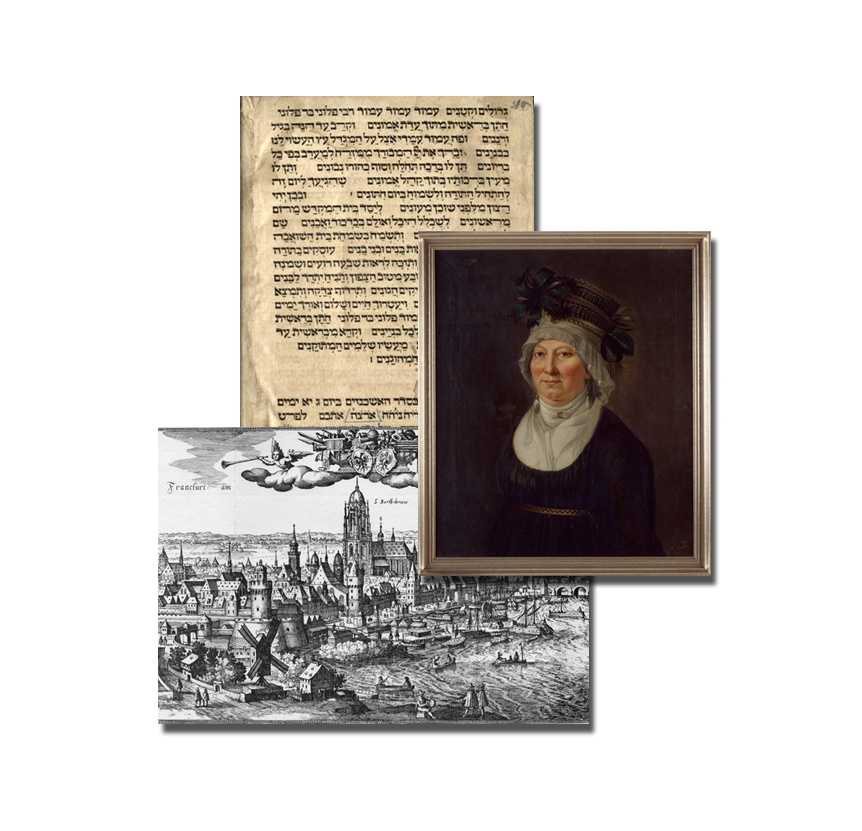

The late sixteenth century saw the renewed growth of a few urban Jewish communities, such as that of Frankfurt am Main. New Gemeinden also emerged, such as in the region of Hamburg and Altona, where several different Sephardic and Ashkenazic communities were founded in the Early Modern period, among them synagogues and Jewish cemeteries such as the one in Wansbek.

The Early Modern era was also marked by Johannes Gutenberg’s invention of book printing, which also transformed the Jewish world. Thanks to this new ease of access, sacred texts and practical religious books reached new categories of readers. Yiddish-language books now catered specifically to women, for instance.

Chaim Schachor was one of the first Jews to print Hebrew books in Germany.

During the seventeenth century, a small few successful businesspeople obtained residency in cities by offering their services to ruling families. As “court factors,” they financed their lieges’ wars and luxury lifestyles. Court Jews, including women, used their influence to protect and support Jewish communities.

One famous example is the daughter of the court factor in Hohenzollern-Hechingen, whose name was Karolina, or in Hebrew Chaile, Kaulla.

In the eighteenth century, the prospect of Jewish intellectuals playing a role in culture and the humanities became more relevant. Although fame and recognition as great philosophers or successful writers remained out of reach for most Jews, the Age of Enlightenment had an major impact: For the first time in history, the discourse around equality was no longer limited to Jewish participation in the economy, but also dealt with Jewish involvement in culture.